Pacific Fishing, Nov, 99 (pg 52, 56-58)

Value Adding, More for Your Fish

November 1999, Page 52

By Susan Chambers, Michel Drouin, Helen Kitchen Branson,

Tim Matsue, Kathleen Menke, Brad Warren, and Jeb Wyman

From automatic pinbone removers to inspired ideas for ready-to-eat seafood, value adding has become a kind of Holy Grail for seafood producers. Fishermen are building boats designed specifically for top-quality handling and freezing. Producers are scouting out wider markets through online auctions, smoking their fish, and finding ways to sell incidentally caught fish that lacked markets in the past.

The Great Pinbone Race

Competing Machines Can Pull or Cut Out Salmon Pinbones

Ray Wadsworth has become Alaska's pinbone champion, but he's still

got sharp competition in the race to market pinbone removal machines -

a technoloogy that many expect will increase the value of Alaska salmon.

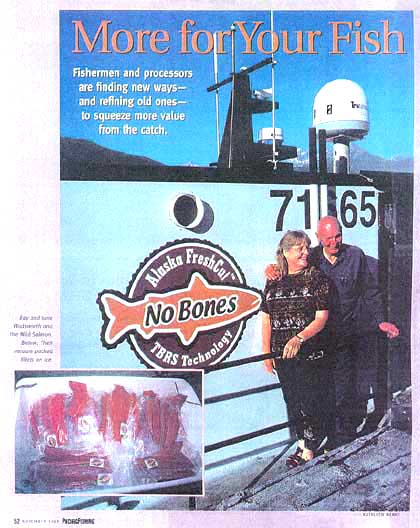

When the irrepressible Ray Wadsworth brought home 100,000 pounds of 100% bone-free, vacuum-packed salmon fillets from Southeast Alaska last August, he wasn't just demonstrating the viability of his pinbone-removing machine. (see related artice page 56) He was staking a claim in the coming revolution in the wild-salmon market: boneless fillets.

Pinbone removal isn't a novel idea. FTC of Sweden has offered

a hand held device for removing pinbones since 1986, the Ergo-LIght.

Rocotech, also of Sweden, and Rapro, distributed by Inventive Marine Products,

are other hand-held devices

currently on the market. And when your labor is inexpensive enough,

needle-nose pliers do the job. In fact, many Alaska fishermen associate

eroding salmon prices with lines of Chilean fish-farm workers armed with

pliers, busily producing

picture-perfect fillets.

Until recently, though, there hasn't been a machine prepared to compete

with those

workers- a machine that can handle the 100-million-plus wild salmon

that Alaska

fishermen haul in each summer. Ray Wadsworth's machine, and the

machines below,

will be among those competing to answer the call.

[following were descriptions of Pinbone pulling machines: Carnitech,

Redbow, and

Trio, followed by TBRS:]

Slice or Pull

Wadsworth's machine is the only salmon pinbone-removing machine that

is based on

cutting out pinbones rather than plucking or pulling them out.

Choosing this approach was a gamble, and Wadsworth knows it. The

problem is

that the process creates a fillet with a slice down its length-a cut

almost down to the

skin-where the strip of pinbones was removed. The 100,000 pounds

of chum fillets

he brought down on his floating processor Wild Salmon are such fillets.

No one

knows if consumers will warm to the product.

But Wadworth is optimistic. He liked to invoke the example of

the pitted olive, a

product that was strange and new when it was first intorduced because

the olives had

holes in them. The pitted olive, of course, was embraced by the

public. Similarly, he

thinks consumers will embrace his unique fillets.

He also says that the slice in the fillets tends to "heal," especially

after freezing in a

vacuum pack, much the same way that whitefish fillets in a block tend

to bond to

each other.

Wadsworth traded the liability of a slice in his fillets for the assets

he sees in his

approach. he learned early on that wild salmon pinbones cannot

be pulled-they will

break off-before a fish has gone through rigor, the stiffening of muscles

that affects all

muscle tissue after death. The onset and duration of rigor depends

on variables such

as the temperature of the fish and how much it has struggled before

being landed.

Rigor softens the tissures that anchor pinbones in salmon.

By cutting pinbones out instead of pulling them, Wadsworth's machine

can produce a

boneless fillet from a fish right out of the water, creating a fresher

product and utilizing

more of the resource, he hopes. He's sold 90 cases of this season's

fillets so far, and

"the word we're getting is that the product is beautiful, best thing

they've ever seen,"

he says.

Yet despite the beautiful fillets produced by Wadsworths TBRS (Total

bone

Removal System) and the other manufacturers, not every major player

in the salmon

industry is rushing out to install machines. Bill Grabes of Tridents

Seafoods

acknowledges that his company is interested in a pinbone-removing machine,

but "we

haven't seen anything that's perfected enough for us to want to spend

the money."

They're seeking a machine with speed, accuracy, and reliability.

Pacific Fishing

Pinbone Wizard: Ray Wadsworth Goes to Market

by Kathleen Menke

On board the Wild Salmon with the Pinbone Wizard

For 10 years, Ray Wadworth kept a salmon skeleton in his dresser drawer,

a

reminder and study tool as he grappled with a problem that has cripples

the

wild-salmon industry in recent years. As a salmon fisherman,

he says, "I found I

wasn't able to make the kind of money fishing I was accustomed to making."

With

boneless Chilean farm-raised coho salmo fillets available everywhere,

Alaska's

salmon producers needed an affordabler way to pull out pinbones and

compete with

Chile's cheap labor costs.

Wadsworth, who is also an inventor has become Alaska's champion in the

technological race to develop a pinbone-removal machine. This

summer, Wadsworth

and his engineering and processing crew out of Sequim, Washington,

plied Southeast

Alaska's waters from Haines to Sitka aboard their floating processor

Wild Salmon,

cranking out the freshest, juiciest bonleless salmon fillets ever to

sizzle on an outdoor

grill. Southeast Alaska locals have been snapping up the priced-right

test packages

of keta (chum) and sockeye fillets, finding that fresh, boneless fillets

are not only tasty

but also an efficient use of freezer space.

Known as the TBRS (Total Bone Removal System), Wadsworth's new machine

is

one of several competing pinbone-removal devices, but it's the only

one that does the

job on fish that are fresh out of the water (see related article, page

54). removing

pinbones from fresh salmon without destroying the flesh was once deemed

an

impossible task; the firm, fresh flesh would tear or the pinbones would

break off

when they were pulled. Even now, other pinbone-removal

systems require that the

fish be a few days old and soft, or frozen first and then thawed before

the pinbones

can be pulled.

The secret in the Wadsworth process is in the cutting of the bones and

the leaving of

a narrow trench where pinbones and a small amount of flesh are removed.

"If all

goes well, this fish will be sold to a niche market looking for a premium

products,"

says Wadsworth, who is known affectionately to his friends and associates

as the

Pinbone Wizard.

The pinbone-removal machine is his latest challenge in a lifetime of

tinkering and

inventions dealing with fishing and boat-building. Born in Seldovia,

Wadsworth

began fishing commercially with his family in Cook Inlet and Kachemak

Bay. At an

early age, he invented fishing strategies and unique gear configurations

to work the

spots that other fishermen avoided due to particularly harsh and challenging

conditions.

Later he started Kodiak Marine Construction, a boat-building and fabrication

business now based in Sequim, where he fitted his seiner with a jet

engine. The

seiner Order of Magnitude made the run between Seattle and Ketchikan

in a mere

17 hours, achieving speeds of up to 50 miles per hour.

Wadsworth took his idea for a pinbone machine to the Alaska Science

and

Technology Foundation, which contributed $1.5 million. Wadsworth

put up $3

million of his own money and in-kind contributions to develop, test,

and refine the

prototype pinbone-removal system and to develop markets for the new

product.

The foundation figures Wadsworth's invention shows promise for Alaska's

fishing

industry.

Early problems that surfaced with the pinbone-removal machines were

addressed

and resolved, generally with minor but innovative adjustments done

on the spot by

Wadsworth and co-inventor Ed Heater. While one of their pinbone-removal

machines was tested aboard the Wild Salmon, another operated in a shore-based

processing plant in Haines, Alaska.

"Haines fisherman Brian O'Riley heard about our efforts and suppliled

me with free

frozen fish to fillet all last winter for testing the machines,"

says Wadsworth. "Brian

took the initiative to attract the testing operation into an existing

facility in Haines

where a cooperative arrangement was set up with a local roe-processing

company,

Seapak, while Wild Alaska Salmon House, the new company formed especially

to

market pinbone-out fillets, made and packaged their new product from

the freshly

caught, highest-grade, primarily keta carcasses."

Wadsworth brought his own special personal touches to the organizational

efforts of

the local fishermen in Haines who have been working hard the last several

years to

develop their onshore processing facilities despite a shortage of capital

and

experience in processing management. When the madness of the

fast-paced fishing

season tended to put fishermen, tender operators, and processors into

stressed

moods, Wadsworth would remind all that "there is a solution to all

problems, and that

solution is sommunication. Seek first to understand, then to

be unederstood."

Machines would get fixed. People would get shuffled. Several

extremely independant

individuals and organizations pulled together in cooperation.

"A fresh keta makes the juiciest, tastiest salmon fillet," says Wadsworth.

Even

doubting locals who usually snub a keta in favor of sockeye, king,

or coho started

placing their orders after tasting a TBRS-produced chum fillet, marinated

and fresh

off the grill.

"The machine is working incredibly well," says Wadsworth. "It's

bordering on being

unbelievable. To watch a whole fish go in and these beautiful

fillets come out is quite

gratifying." With minor adjustments, the machine can be used

on all species of

salmon, and even other kinds of fish. "With a small adaptation,

it'll be able to do

cod," he says. One pinbone-removal machine can fillet and remove

all the bones of

headed-and-gutted salmon at the rate of 24 fillets per minute.

The work aboard the Wild Salmon last summer was performed by a crew

consisting

of Wadsworth, his wife Jane, two sons, three daughters, significant

others, and a

multitude of friends. The unbelievably cheerful processing crew

operated much like

the well-oiled pinbone-removal machine itself. They were actually

singing along with

opera music while being photographed for this article.

Trimmers swiftly touched up the boneless fillets as they exited the

pinbone-removal

machine sporting a narrow trough, like a pinstripe, along their length,

which is pressed

closed when the fillet is turned over and smoothed. Any stray

pinbones, of which

there are only a few here and there in one out of every 10 salmon or

so, were hand

pulled with needle nose pliers by the trim line. At the end of

the line, fillets that

passed inspection were slipped into vacuum-packaging bags, sealed,

and placed into

a brine trough where they came out the other end thoroughly quick-frozen.

Another crew member placed the TBRS "No Bones" label on each fresh

vacuum-packed, frozen boneless fillet, weighed them, and packed them

into 25

boxes. The boxes were labeled with the date and area of the catch,

the name of the

fisherman who caught them, and the net weight of the fish, and were

placed into the

cold-storage hold. At the end of the season, when the onboard

printer was finally

working properly, a color photo of the fisherman who caught the fish

was also

inserted into each box of fillets processed from that fisherman's specific

catch.

A weeks worth of processing nearly filled the floating processor's 40,000-pound

hold

when the fish were running strong. Six van-loads of TBRS salmon

fillets were

shipped to cold storage in Seattle for delivery into the hands of test

marketers for the

upcoming year. "There is a clear difference in quality between

fresh Alaska salmon

and the farmed product," Wadsworth notes.

According to Laura Fleming, public relations director for the Alaska

Seafood

Marketing Institue, automated systems such as this will help Alaska

fishermen

compete with the farmed-salmon market. "An enourmous

market is emerging for

boneless salmon fillets. Consumers want food that's quick

to prepare, tasty, and

close to ready to eat, and they don't want bones. The machine's

success would

enable a domestically processed product to compete with imported, boneless

products."

Wadsworth patented his machine four years ago. If the project

proves successful,

the company must repay the Alaska Science and Technology Foundation

for the

money it has invested in the project. The grant also requires

Wadsworth to sell or

lease the machines exclusively in Alaska for three years after completion

of testing.

Wadsworth speculates that the finished pinbone-removal machines will

be leased

rather than sold. "For one thing, we can service the machines

for the leaser and make

the necessary modifications as we evolve."

Wadswworth and his crew will be looking around and considering their

options for

the best places in Alaska to continue their testing next fishing season.

Alaska Fisherman's JOURNAL

Ray's Way - In search of the perfect wild salmon fillet

by Bruce Buls

When RayWadsworth designed and built a machine that cut completely boneless

fillets from salmon, he thought he had done what needed to be done.

After all, finding

a way to remove salmon pinbones mechanically had been the industry's

Holy Grail for

years.

Called the TBRS (total bone removal system) 50, his complex processing

machine

was tested during the 1998 Alaska salmon season by American Seafoods,

but Ray

wasn't happy with the way his machine was utilized. He was also

underwhelmed by

the level of industry interest in his invention.

After that inaugural season Ray realized he would have to do more than

just develop

a machine that removes all bones, including the ever-allusive pinbones.

"We can't just build a machine," he said after that first season.

"We have to have a

whole sytem. The industry need to be led, not pushed. I

think I can show how the

product should be done."

So in typical Wadsworthian fashion, Ray set out to do just that.

Having already been

a fisherman, boatbuilder, and designer/inventor-to name of few of his

pursuits-Ray

took the next logical step and became a processor.

I told ASTF that we'd built a beautiful airplane," says Ray "but we need an airport."

ASTF is the Alaska Science and Technology Foundation, an Anchorage-based

not-profit that has invested about $1.5 million in TBRS technology.

Last winter, Ray and his son, Doug, found a 74 foot Navy-surplus landing

craft and

converted it into a floating salmon processor.

When they found the boat in California it didn't even have engines,

let alone all the

other stuff you need for a processing operation. That was Christmas

time, and the

salmon season was only a few months away. But such impediments

mean little to a

man who's made a career out of overcoming obstacles.

After surviving what he describes as "the worst ride of my life" up

the coast to Port

Angeles, Wash., in March (during the same storm that twice grounded

the New

Carissa), Ray and his boatbuilding company, Kodiak Marine Construction

finished

outfitting the newly named Wild Salmon with the necessary tanks, tables,

machinery,

bunks and evertything else needed for a summer of processing salmon.

They did the

whole job in two and a half months.

Along with the TBRS 50, they installed a Baader 417 header at the beginning

of the

line. At the other end, they added vacuum-bagging and brine-freezing

equipment.

Finished product was boxed and sent below to the cold storage.

Ray says his machine can process 24 fillets a minute. Each fillet

must also be trimmed

by hand to remove the bottom of the belly flap and individually inspected.

Although the machine had the capacity to handle 12 fish a minute, the

bagging,

freezing and casing operation couldn't mainain that pace. Even

so, the crew put up

about 150,000 pounds of frozen, boneless chum fillets last summer.

Ray himself worked onboard virtually all summer. After being away

once for a

week, he says he was relieved and gratified to return and find that

fish had been going

through the line just fine without him.

It was a tight crew. Up to 20 people were squeezed aboard the

crowded boat,

including Ray's wife, tow daughters, two sons, and a foster daughter.

People slept

everywhere, even on the console in the pilothouse. As has often

been the case with

him, it was a family affair. In fact, his father, Gene, and his

son, Doug, are the official

owners of the Wild Alaska Seafood House, the company that owns the

boat.

The boat and crew headed north from Washington on July 1 and arrived

in Lynn

Canal a week later.

Things got off to a rocky start when a tender delivering their first

load of fish ran

aground and sank. Ray says they ran down the canal and found

the floating totes

with fish, which they recovered and processed.

"I knew then that we were going to have to work for them," Ray recalls.

They may have had to work for the fish, but they didn't have to pay

for them.

Processing primarily chums, they took fish that had already been stripped

of eggs-fish

destined for dumping or the grinder. Even so, Ray insisted that

fishermen deliver "fish

that you would send to you family and friends for Christmas."

Catching and handling fish to maintain premium quality before processing

is the first

step of the Wadsworth formula for the success of the Alaska salmon

industry. The

second part is technology-his machine-and the third part is marketing.

"I realize we had to have numbers one and three after I developed the

technology,"

says Ray

Successful marketing relies on numbers one and two. It also means

selling the

fishermen along with the fish. Ray puts the name and a digitized

photo of the

ressponsible fishermen on each box of fish. It's the Bruce Gore

model, except the

fish are boneless and less expensive.

"Consumers recognize accountability," Ray says, adding that being identified

had a

big impact on the fishermen, too. "They really began to go all

out to produce nice

fish."

Producing affordable, boneless "nice fish" that will make Alaskans pround

and

Americans hungry for more is Ray's ultimate goal. If and when

this happens, he

hopes the industry he knows and loves will survive.

"I told Lt. Gov. Fran Ulmer that the industry can go two ways.

Either 90 percent get

out and 10 percent survive, or we raise the value so everyone can make

a living.

"Fishing is like a paradise," Ray muses. "It's fun and it can

be prosperous. I'd kinda

like to see this thing survive for another generation."

Before his current crusade, Ray spent many years trying to organize

Alaska seiners

through the creation of the United Seiners Association. His dream of

a marketing

cooperative like Sunkist oranges or Blue Diamond almonds didn't materialize,

but

setbacks don't discourage Ray for long. He just finds another

way to push the

envelope.

Ray's lifelong contributions to the Alaska fishing industry are being

recognized this

year by National Fisherman magazine, which has selected him as one

of this year's

three "Highliners." The award will be presented during Fish Expo

in November.

The Spokesman-Review

Spokan Wash/Coeur d'Alene, Idaho

Wednesday, Jan 12, 2000

Section D, Food Finds

Chum? Yum

With wild salmon season having ended a few months ago, all we've got are the farm-raised fish for the winter, right?

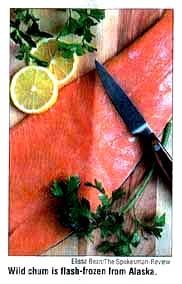

Not Necessarily. North Pacific Trading Co. distributes boneless, vacuum-packed fillets of wild Alaskan keta (chum) salmon--moderate in fat, and delicate in flavor--that are flash-frozen at sea for freshness.

So this winter, you don't have to buy the farmed.

Price: About $4.00 per pound (average weight 2 pounds).

Available: At area Rosauers, Yoke's and Super 1 stores.

The Wall Street Journal / Northwest

Wild Salmon Run Ahead in Taste Test

By Anne Reifenberg

In Seattle, the natioin's salmon capital, most people have had their fill of the interminable debate over how to restore at-risk runs. but they still have hearty appetites for the fish, which puts them in the thick of another Northwest polemic: What kind of salmon should end up on our plates?

To put the matter to the taste test, The Wall Street Jounal arrangedd for salmon experts to sample three typed-wild, hathery-raised and farmed. The results surprised even the parrrticipants.

Taste aside, many environmentalists argue in favor of the wild varieties, because if people eat and enjoy them, a consituency will build for saving those that are threatened and endangered. Commercial fishermen naturally agree with environmentalists, since it's good for their business, while some connoisseurs prefer undomesticated fish for their consistency and flavor.

But increasingly, the salmon we eat hails from hatheries and farms. And some say the domesticated fish industry is posed for enourmous growth. "It will totally displace the commercial fishery one day," says Dan Swecker, a Republican state senator from Rochester and president of the Olmpica-based Washington Fish Growers Association, which has 50 members.

What matters to most folks, however,is basic. "I don't care where it was born," says Donna Black, an artist who eats salmon in ine form or another at least once a week. "I care about how it tastes."

A Taste Test

So on to the Dahlia Lounge, a restaurant in Seattle, where chef Matt

Costello, using just a bit of salt and olive oil, baked center cuts from

three fish: a king from a hathery in British Columbia, a king from a farm

in Washington and a wild king caught off the coast of Sitka, Alaska.

the six panelists-two commercial fishermen, a fisheries consultant, Amazon.com Inc.'s cookery editor, a Washington Fish and Wildlife commisioner and a conservationist-weren't told which cuts were which.

All agreed that one was superior: the wild king. "I was surprised that I like it so much better than the others," says Lisa Pelly, the commisioner.

few on the panel guessed that they had favored the wild one. Rebecca A Staffel, Amazon's cookery editor, says she didn't have a clue. "I knew what I liked best, but I had no idea whether it was born in captivity or out in the ocean."

The wild fillet, says Tim Stearns, the conservationist, was flakier than the others, "but the indidvidual parts retained their integrity. The farmed stuff just mushed in the mouth."

Eric JOrdan, who trolls for salmon in the waters off Alaska, says he was taken aback that he couldn't identify the type of fish simply by taste. "I was really surprised I couldn't tell the difference," he says. Since he has a trained eye for salmon, he made an effort not to look too closely at the samples during the tasting.

The other fisherman, Harold Thompson of Sitka, did look. "If you know fish, it's really easy to tell," he says. "But if you don't know you should always ask what you're being served, because there's a big difference." Adds John Foss, the consutant, "People who like steak aren't going to lik wild salmon as much, because it can tend to fall apart more." [more flaky]

What are the habitat differences among the three? Wild salmon live their entire lives outside of human control. Hathery salmo are conceived in captivity, sometimes of wild parents, and released when they are smolts, or juveniles mature enough to make the long and arduous trip to the Pacific Ocean. And farmed salmon are raised entirely in floating pens.

Dumb and Dangerous

Mr. Costello, like many chefs in the Northwest, doesn't serve fasrmed

salmon. Fish reared in saltwater pens don't get a lot of exercise

and so produce cuts that are mushier, he says, and less flavorful.

Greg Higgins, owner of Higgins Restauraunt in Portland, also shuns farmed salmon. While he does serve hathery raised fish, he prefers the wild version. Among his objections to hathery products: they come froma narrower gene pool."

IN fact some scientists contend that hathery fish are so much stupider than their wild cousings that they pose a danger to the species. Because of the trouble free environment in which they spend their early days, these scientists say, hathery salmon probably don't learn how to dig nests or elude bears or other predators. According to this argument, the wild salmon is the product of thousands of years of a survival-of-of-the-fittest winnowing, and it's risky to allow the domesticated to mingle with them.

It may be too late, though, to even continue quarreling, since hatheries have been around for more than 100 years. (Only recently, however, has the idea taken root that hatchery products might supplement runs in danger of extinction. The theory was first tested in pilot programs in the early 1990s. Most of those, sponsored by the U.S. fish and Wildlife Service, were conducted in the Snake River Basin in Idaho, where federal wildlife agencies first noticed the serious decline in fish runs. Officials say it's still to early to tell if those programs have succeeded.)

Fresh Debate

The farmed salmon debate isnewer, and livelier. Critics complain

that farms damage the natural ecosystem by producting unnatural concentrations

of wastes, disease and antibiotics. Another concern is that farmed

fish that escape from their floating pens prey on the wild fish or breed

with them and weaken the system.

Mr Higgins also worries that the existence of salmon farms will reduce public intererest in saving the wild salmon. "Having so many farms can easily lull people into thinking that they don't have to worry about the wild population, because there are all these replacement fish around," he says.

but so far, government regulators have come down on the side of the farmers. Last year, for example, environmental groupls challenged the issuance of Department of Ecology permits to two farms that raise Atlantic salmon. However, the Washington Pollution Control Hearings Board ruled that salmon farming in the Puget Sound region didn't seriously endanger native salmon or the environment.

Mr. Stearns, director of the Northwest office of the National Wildlife Federations says that with farms and hatcheries likely here to stay, salmon aficionados should probably just eat what they like- so long as they eat a lot of it. "We have a motto," he says. " 'Two in the river, one on the grill.' If people demand good salmon, theyll want to protect the salmon we have."

[As a side note from the webmaster, don't worry, Alaska's salmon are abundant, and in no danger, these past few years Alaska has set it's records for the most salmon recorded this century! You can examine this info at the "Alaska dept of Fish and Game"]

Fish Bowl

The six panelists graded each fillet by number, with 10 the highest

mark. Though most couldn't guess which cut was which, they preferred

the undomesticated [wild] salmon.

Wild-caught off the coast of Alaska

texture 9.0

flavor 9.5

overall 9.7

comments: beautiful color; melts in your mouth;

mellow

Hatchery-supplied by the Wash. Fish and Wildlife Dept.

texture 5.2

flavor 6.0

overall 5.3

comments: fishy tasting: firm and sweet; too firm

Farmed-born and raised in a cage in Washington

textrue 5.0

flavor 5.5

overall 4.83

comments: greasy; fishy but tender; watery

1999 Highliners Award

by Bruce Buls

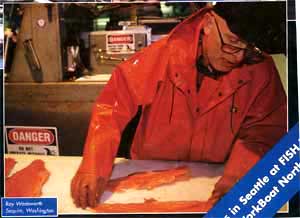

They call him the Pinbone Wizard. While the name is a clever turn

on The Who's

"Pinball Wizard," it's also surprisingly apt. For one thing,

he invented and built a

machine that others had been talking about for years: an automated

pinbone remover.

His machine, the TBRS 50 (total bone-removal system) pulls headed and

gutted

salmon in one end and flips out boneless fillets from the other.

That's boneless, as in

no backbone, no belly bones and no pinbones, the most elusive

and problematic

bones of them all.

Creating a complex, sophisticated machine like that in a boatbuilding

shop on the

outskirts of Sequim, Wash., is clearly an act of wizardry.

But Ray Wadsworth also looks the part of a wizard. He's completely

bald, has a

bright twinkle in his eye and seems perpetually amused, or perhaps

bemused.

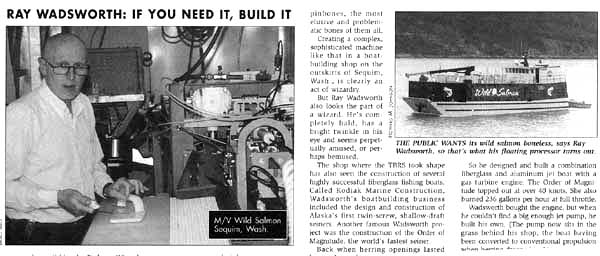

The shop where the TBRS took shape has also seen the construction of

several

highly successful fiberglass fishing boats. Called Kodiak Marine

Construction,

Wadsworth's boatbuilding business included the design and construction

of Alaska'a

first twin-screw, shallow-draft seiners. Another famous Wadsworth

project was the

construction of the Order of Magnitude, the worlds fastest seiner.

Back when herring openings lasted longer than a few hours, the fastest

boats had a

distinct advantage. Spotter pilots would locate a school of fish,

and the race would

be on. Being a competitive sort, Wadsworth definitely wanted

to be first on the fish.

So he designed and built a combination fiberglass and aluminum jet boat

with a gas

turbine engine. The Order of Magnitude topped out at over 40

knots. She also

burned 236 gallons per hour at full throttle.

Wadsworth bought the engine, but when he couldn't find a big enough

jet pump, he

built his own. (The pump now sits in the grass behind his shop,

the boat having been

converted to conventioinal propulsion when herring dropped to $200

a ton.)

It's his sort of can-do attitude that has characterized Wadsworth's

entire career. He

credits his attitude and ability to growing up in a fishing family

in Alaska.

Born and raised in Seldovia, the son of a fisherman (his father, Gene,

is something of

a legend in his own time), Wadsworth remembers that "if you needed

it, you built it."

And if you had an idea to try something different, you built that.

too. For example, he

says his dad was the first person that he knows of to put a water jet

in a boat.

By the age of four, Wadsworth was a fixture aboard the Sea Scout, his

father's small

wooden boat. He's been fishing ever since. H's longlined,

driftnetted, setnetted, and

seined for salmon and herring fromn Southeast to Kodiak and Togiak,

where he still

fishes.

During the halycon days of herring sac roe fishing he is reported to

have grossed $1

million a year.

But when markets collapsed, Wadsworth says, he went to one of the gear-group

leaders in Kodiak and asked him what he was doing to help raise the

price. The

answer was, in effect, nothing.

"That winter," he says, "I decided that since nobody was doing anything, I would."

So he formed the United Seiners Association. "My dream was to

throw together a

large group of fishermen and form a cooperative like Sunkist [oranges]

or Blue

Diamond [almonds]."

Finding the independent attitude of fishermen frusterating, Wadsworth

focused on his

next goal: raising the value of Alaska salmon to more closely match

their inherant

value. The strategy: bonelessness.

"The fish has to be boneless," he says. "The farmed fish market

has already

established that."

American Seafoods tested his machine during the 1998 salmon season,

but

Wadsworth doesn't believe it was used properly. He was also underwhelmed

with

interest from traditional salmon processors.

So, with more help from the Alaska Science and Technology Foundatioin,

which has

invested about $1.5 million in the TBRS, he and his family set up their

own floating

processor, the Wild Salmon. They spent last summer in Lynn Canal

putting up about

150,000 pounds of boneless vacuum-bagged, brine frozen chums (Wadsworth

prefers to call them ketas).

The idea was to demonstrate the effectiveness of the machinery and the

feasibility of a

small operation that works very closely with fishermen delivering high

quality fish.

Wadsworth says the survival of Alaska's slamon industry hangs in the

balance. "I told

Lt. Gov. Fran Ulmer that the industry can go two ways: Either 90 percent

get out and

10 percent survive, or we raise the value so everyone can make a living.

"Fishing is lke a paradise. It's fun, and it can be prosperous.

I'd kinda like to see this

thing survive for another generation."

HOME HEALTHY

NATURAL PRODUCTS

PROCESS FISHERMEN

COMPANY CONTACT

IN THE NEWS